Foreword

Drones are widely perceived as gadgets of leisure that are sent to the skies to shoot impressive aerial photographs and high-definition video. While they’re commonly used for entertainment, our

study reveals that there’s also a range of business applications for drones across various industries, resulting in a significant potential market that can be expected to grow exponentially. As advisers, this is a particularly appealing aspect of emerging technologies: how can they be applied to make our clients’ operations more effective? Finding the answers to this question is why PwC was happy to contribute to this study and is pleased to share the results.

Drone photo and video capabilities are widely applied in the media, entertainment and both public and private security sectors; yet applications are much broader when sensor-equipped drones

are combined with data & analytics and machine learning to make use of the vast amounts of information drones can provide. This combination opens up drone use to industries like power generation, utilities, logistics and agriculture, allowing data to be captured and analysed in ways that were previously difficult or impossible. Drone technology has largely surpassed human intervention for faster, easier and cheaper data collection. At an estimated market value of 409 million euros, the potential for drones in Belgium is undeniable.

The Belgian drone ecosystem is experiencing exponential growth, with players defining their role in the value chain and exploring ways to meet users’ needs. Some focus on the hardware and software, while others offer ‘drones as a service’. They all act as catalysts for the implementation of drones in our economic landscape. They’re the enablers which bridge the gap between businesses and drone technology, playing an essential role in accelerating the use of drones in commercial applications.

Although basic rules are in place, the legal framework around drones is still evolving. With great technology comes great responsibility: flying a drone not only implies compliance with general regulations around drone use, but also with rules on privacy and security. Further evolution in these relatively new regulations can cause ambiguity, resulting in uncertainty and conflicting guidelines. Cooperation and alignment between various Belgian regulators is therefore essential.

As in other areas, drone use will benefit from a harmonised, EU-wide legal framework. Once these laws are in place and as the technology continues to evolve, we’re confident that organisations will look to the skies and that drone technology will become an integral part of standard business operations.

“Boys and their toys”… Drones are toys, but they’re also highly sophisticated tools that enable companies to optimise their value chains.

However, for new technologies like drones to become valuable and integrated contributors to a company’s business model, a number of conditions must be fulfilled. Think of legislative frameworks, adapted operational processes and cultural/educational changes.

Technology evolves at a much higher speed than legislation. This means that the competitive advantage that companies can create in any given country is directly related to the speed at which that country can adapt its laws. This represents immense opportunities to the fast – and equally significant threats to the slow.

For the first time ever the Belgian drone ecosystem has been analysed. This study shows the economic potential of drones in euros, jobs and more.

Today, drones are sophisticated observers. They can capture data more efficiently than traditional alternatives. They can also significantly reduce risks associated with specific observations, eliminating the need for humans to be physically present in hazardous environments.

The drones of tomorrow will evolve from mere observers to highly automated, autonomously operating and even decision-making tools. The sky’s the limit for the applied science of flying robots – or “dronebots”.

In the immediate future, we need to address our first challenge: integrating the products and services of current drone-(application)producing companies into the value chains of other businesses. A huge effort needs to be made to trigger the imagination of business leaders. It’s that imagination that’ll drive the application of drones into current business processes, allowing Belgian companies to take a competitive lead and by doing so, create employment and economic prosperity in our country.

This is a study about drones, but more importantly it’s about the implications of drones on us as individuals, as organisations and as a country.

Executive summary

It looks like our 21st century will be the century of robots, with a lot of buzz concerning a fast growing subfamily of these machines, namely drones.

PwC and Agoria worked together to gain insight into the developing drone ecosystem in Belgium, and more specifically the potential for the commercial use of drones. This report is the result of interviews with more than 50 key stakeholders, of both current and potential drone users, in eight industries over the last five months. It also leverages market knowledge and insights from both PwC and Agoria.

The young Belgian drone ecosystem is rich, both in assets and challenges. Many initiatives have been set up, but now the challenge is for players to join forces, work together and learn from each other. Everyone in the ecosystem shares the same purpose; to enable the drone economy in Belgium to grow and reach its full potential. PwC and Agoria estimate the total size of the potential market to be worth 408.9 million euros annually. The gap between that potential and the reality is still significant, and therein lies opportunity.

As the study’s use cases demonstrate, drones can do much more than take pictures. In combination with other emerging technologies (such as artificial intelligence (AI)), inspections can be undertaken in a cheaper, faster and safer way. Harvests could be optimised as part of precision agriculture and surveillance could be carried out more quickly and efficiently. Drones might be just a tool, but in combination with the right technology and/or equipment (e.g. cameras, sensors and robot arms), the number of applications is enormous and will continue to grow in the future. It’s crucial that businesses embrace innovation and start experimenting, and seek to learn from each other, across geographical borders and industries.

A much-needed European regulation, with respect for privacy, safety and ecology, is in the making. It should further strengthen the enabler role that the current Belgian legislation is picking up, albeit with mixed success. If the opportunities offered by the drone economy are fully embraced by all with a joint vision and passion, its success will result in the creation of new jobs and prosperity, and this for many years to come.

Introduction to drones and the Belgian market

You’ve probably seen them buzzing around above you: drones. They’ve become a common sight over the past few years and people are using them for all sorts of purposes: kids to play, adults to take aerial vacation selfies, companies are training their personnel in drone use and multinationals are investing in drone equipment and software development. Why are drones so rapidly becoming part of our lives? Let’s look back at their beginnings.

The first drone was the 1918 Kettering Bug, developed for defence in World War I. It was used as an aerial torpedo to reduce the need for manned flights over hostile territory. Between the two world wars, the Reginald Denny series were the first drones produced on a large scale, and were used as aerial targets for training anti- aircraft gunners. In 1946, B-17 Flying Fortresses were transformed into drones for collecting radioactivity data during nuclear tests. Decoy drones, such as the ADM-20 Quail, were developed during the Cold War to help manned planes fly safely into defended airspace.

The use of reconnaissance drones in the Vietnam War highlighted the main purpose of drones, then and now: to gather information. All drones have a common denominator: they accomplish

a task that would prove difficult or even impossible for a human.

It’s essential to choose the right type of drone for the task. When people talk about drones, they’re usually referring to flying remotely piloted vehicle (RPV) systems. In addition to aerial drones,

industries also make use of ground, naval and space systems. As these systems are starting to communicate and collaborate, a new constellation of unmanned service devices (USDs) is growing.

There are three main types of aerial drones: rotary wing, fixed wing and lighter-than-air. The most common drone configuration is multirotor with four, six or eight propellers. The multirotor (rotary wing) type has been available for about a decade, thanks to the development of small, powerful and affordable electronic components, also used in smartphones. It’s an unstable and energy inefficient configuration, but it can take off and land vertically. The airplane (fixed-wing) configuration is much more efficient with greater endurance and range, but it needs space to take off and land. Airships (lighter-than-air) don’t need airspeed to generate lift so they can fly almost indefinitely, but they’re very weather dependent.

The need to solve a problem creates the need for a specific technology. An aerial camera can be used by soldiers to look for enemies behind a hill or to inspect damage to power lines. The problem’s different, but the technology’s similar. Like many technology markets, the drone industry is highly problem driven. It has the huge advantage of needing only relatively minor modifications to alter

or advance the technology, instead of a complete development cycle, which can take years. The computational power is miniaturised and is becoming less costly every day. Problems can be solved by connecting the pieces of a puzzle that already exist. Drone technology becoming accessible is the reason for the rapidly expanding market, and explains the use of drones in media, advertising, police work, firefighting, agriculture, construction, energy, transport and more.

Belgium

The Belgian armed forces have a long history of drone use and development. The MBLE Épervier was developed in 1970 as a reconnaissance system. The target drone Ultima and surveillance

drone B-HUNTER are still in use. Two thousand and ten marked the start of the civil drone industry in Belgium, with the launch of the Gatewing X100. The establishment, in 2012, of BeUAS, the Belgian drone aviation federation, was the beginning of a structural collaboration between drone manufacturers, researchers, end users, training providers and the government. One of its major outcomes was the Belgian Drone Legislation of 2016.

The main task of BeUAS was to set up a legal framework for drone operations in Belgium. A legal group of manufacturers, researchers, academics, air traffic controllers, airline pilots and service providers was established. The proposal for a Royal Decree was ready by the end of 2012, but due a lack of clarity around the expected impact of drones, it took until 2016 to put the current Belgian drone legislation in place.

In the meantime, many industries and sector federations have started to work together on dedicated drone market needs or have expanded their current activities to integrate drones. One of the best known initiatives was the establishment in 2013 of EUKA, a non-profit member organisation working to enable the drone industry in Europe, which went on to receive Flemish Innovative Business Networks (IBN) recognition as a drone cluster organisation. Unifly has played a key international role in the integration of manned and unmanned aerial traffic, and many Belgian organisations actively support international bodies such as the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), UVS International (UVSI), the Global Unmanned Aircraft Systems Traffic Management

Association (GUTMA) and many more. Drone use is expected to grow rapidly in the coming years, creating new and complex challenges related to large numbers of drones in a wide variety of applications and markets.

Many questions have yet to be answered. How will airspace be shared with manned traffic? How will huge amounts of data be efficiently and reliably processed and transferred? Which drone applications are feasible and what’s the corresponding return on investment (ROI)? What infrastructure is needed for drone development and operations? Which legislation has to be introduced or adapted to ensure acceptable safety levels? How will the misuse of drones be handled? How can we evolve to autonomous drones?

Using drones not only to collect data, but also as tools for the Internet of Things (IoT), transport, flying robotic arms and more, opens up a whole new range of potential applications. The (r)evolution of drones is expanding into a completely new ecosystem: ‘dronebots’. In this ecosystem, the air-land-sea service devices are part of our everyday lives and their use will be as normal as that of cars today.

About the study

This study focuses on commercial applications of aerial drones. We interviewed over 50 select users and stakeholders in our effort to be as representative as possible, but the study is not exhaustive. The market is constantly developing with new entrants appearing frequently. From our “drone’s eye view”, we present one case study per industry to illustrate the potential for commercial drone applications in Belgium.

The study begins with an introduction to drones, followed by an overview of stakeholders, the potential economic value of drones and how drones can deliver value in the various industries covered. For each sector, we include an estimate of market potential. We also take a closer look at legislation and conclude with the challenges and enablers of this promising ecosystem.

The economic potential of drones

Given the expected impact of drones across various sectors and the wide range of potential applications, we selected a number of industries for which to assess drone use in Belgium, both now and in the future. We asked key players in each industry to share their views, allowing us to provide an overview of the situation.

Similarly, we polled key organisations at the core of the Belgian drone ecosystem to hear their vision of drone evolution.

Seeking to assess the economic potential of drone solutions in Belgium, we based our estimation of the market value on the methodology used in PwC’s ‘Clarity From above’ study on the impact of drones. We performed separate analyses for each industry, based on data from 2016.

For example, to calculate the addressable market value for the Telecom sector, we took the number of telecommunications towers in Belgium multiplied by the labour cost of maintenance and the portion of maintenance activities that can be replaced by drones.

We calculated the total addressable market to be worth 408.9 million euros annually, with the Infrastructure industry, with a value of 176.3 million euros, having the greatest potential.

| Industry | Value* |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | 29.0 |

| Energy & Utilities | 23.3 |

| Entertainment & Media | 45.7 |

| Infrastructure | 176.3 |

| Insurance | 40.6 |

| Security | 30.9 |

| Telecom | 19.6 |

| Transport & Logistics | 43.6 |

| Total | 408.9 |

* Values presented in this table correspond with the 2016 value of businesses and labour in each industry that may be replaced by drone powered solutions, according to PwC and Agoria research.

Stakeholders in the drone ecosystem

There have been significant developments in recent years in the drone ecosystem on a global scale, including the drone legislation framework in Belgium in April 2016.

The following numbers provided by Belgian Civil Aviation Authority (BCAA) provide insight into the level of activity in 2017:

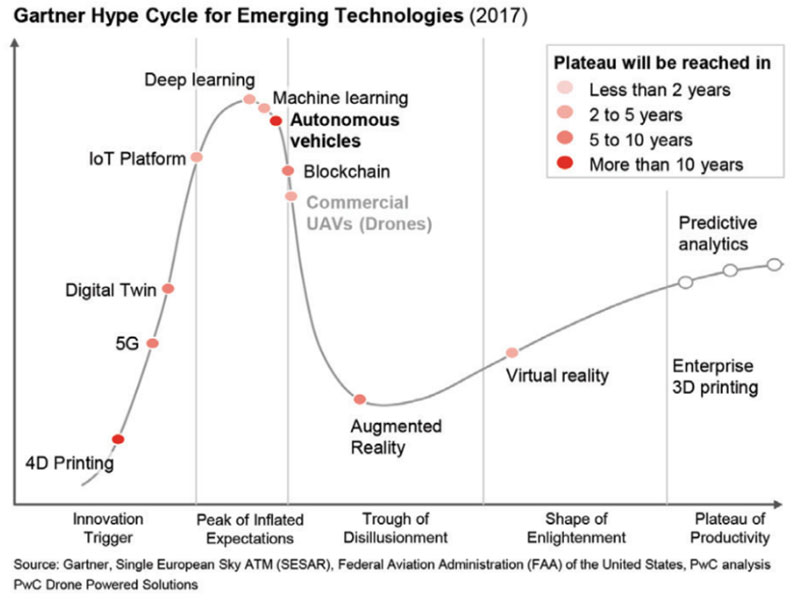

The commercial use of drones is approaching the ‘plateau of productivity’ in the Gartner Hype Cycle, as illustrated in the Figure 3.

This chapter provides insight into the key enabling organisations and initiatives in Belgium that facilitate further development of new value propositions and enhance existing ones.

These industry-specific value propositions are required to realise the potential of an addressable yet largely untapped market, which this study estimates is worth 409 million euros annually in Belgium. Respect for the highest standards of safety and privacy are main priorities.

Figure 4 from DRONEII.com (Drone Industry Insights) provides a recent (2018) overview of the principal drone players around the world, some of which are active, directly or indirectly, in the Belgian market.

DRONEII saw a clear movement towards investment in software in 2017. Companies are realising that it’s not the drones themselves that provide value for users, but the data they gather and its potential application. This is part of the reason behind the dramatic increase in strategic partnerships. Since standalone drone hardware is not the focus of commercial customers when considering drone technology, the industry has shifted towards offering complete solutions. The bundled offering of hardware and software is driving numerous strategic partnerships.

Similar partnerships are also forming in Belgium. The following section examines the key players in the Belgian commercial drone ecosystem, namely

- Manufacturers

- Software

- Infrastructure, testing, incubators and start-ups

- Service providers

- Regulatory environment

- Training & education

- Applied research

- Collaboration, networking & community building

Manufacturers

Production of drones for commercial use is limited in Belgium. However, Belgium is home to Delair, a leading producer of drones in Ghent. Delair formerly Gatewing, was founded in 2008 as a spinoff of the University of Ghent and is now part of the French Delair Group. The Flagship UX11 is produced in Belgium, with over 95% of production shipped worldwide.

Other than drones for education and research purposes (VIVES, KUL and VITO), there are no other known producers of fixed-wing drones for commercial use in Belgium today.

There are several producers of multirotor and helirotor drones, including the well-known Flying Cam (http://wp.flying-cam.com) in Wallonia that’s been manufacturing drones for the film industry for over thirty years. Another longtime producer of multirotor drones is Altigator in Waterloo. Dronematrix has been on the market for several years and manufactures specialised devices like tethered drones. There’s also a growing group of hardware and software companies that enhance standard drones (largely produced by industry leading manufacturer DJI) for business-to-business (B2B) sales and specific use cases.

Most payloads including Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSSs) that equip drones for specific use cases are not produced in Belgium. There are a few local producers that are active mostly in export markets, such as Luciad, now part of Hexagon. Large companies with local or international headquarters such as Nokia and Sabca are also engaging in the value chain, yet it’s unclear how fast this business will grow.

Belgium is strong in electronics and precision manufacturing, so certain specialised skills and parts can be sourced locally.

Software

Drone software is the brain of the drone and tells it where to go and what to do while flying from A to B. To understand and connect the information, the software installed in the drone is complex and operates in a layer-like system. The layers themselves are divided into tiers that perform in various time slots. The layers have to be combined properly to control flight patterns, altitude and other important information for the drone to work and act accurately. This combination of layers is called the flight stack or autopilot. Many studies have shown that it doesn’t matter if drones have different efficiency or mission complexities, they all need effective operating components. The information received has to be analysed inflight.

To achieve unified component communication, a generic architecture must be designed and promoted. The onboard system alone is not sufficient: external middleware and an operating system are necessary. The requirements of firmware and middleware are time sensitive. Firmware operates from machine code to processor and afterward to memory access. Middleware conducts flight control, navigation and telecommunication. The operating system monitors optic flow and avoids interference while simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) searches for solutions and decides the appropriate action based on information received.

Great integration skills are required to meet the growing demand of specific ‘drones as a service’ offerings. Belgium has a significant presence in this area, with good collaboration between industry and research.

A specific software critical for safely managing the expected growth of commercial drone applications is unified traffic management (UTM).

A UTM platform connects authorities with pilots to safely integrate drones into the airspace. Authorities can visualise and approve drone flights and manage no-fly zones in real time. Drone pilots can manage their drones and plan and receive flight approvals in line with international and local regulations. Europe is very mindful of the importance of drone traffic management and is working hard on concepts and the implementation of U-space.

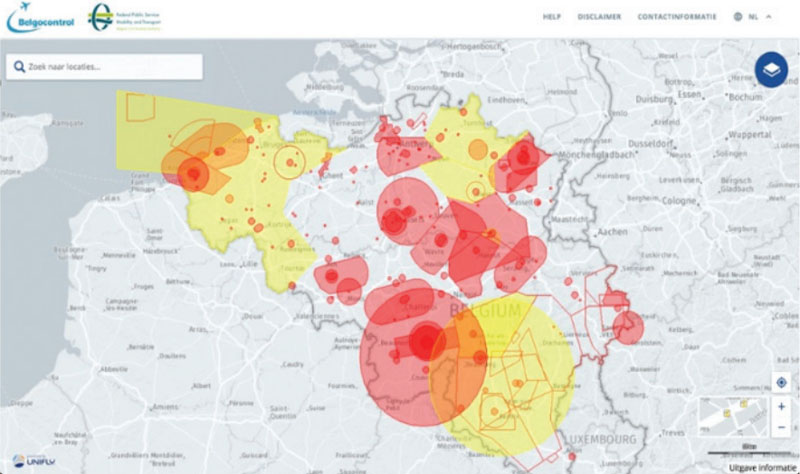

Belgium boasts key players providing UTM solutions, mainly Unifly and IDronect. The BCAA and Belgocontrol, an autonomous public company responsible for the safety of air navigation in the Belgian civil airspace and consequently also of its passengers and the overflown population, jointly launched a tender for a software solution for planning safe drone flight in Belgium. The tender was won by Unifly and phase 1 went live in Q1 2018.

Infrastructure, testing, incubators and start‐ups

A new economy means new requirements. For drones, these involve testing, takeoff and landing, maintenance, recharging, training and much more. Initiatives are currently being undertaken in Belgium, with different stages of maturity and progress. An organisation at the forefront is DronePort in Sint-Truiden.

DronePort’s 15-hectare research and aerospace facility aims to become one of Europe’s leading unmanned aircraft systems (UASs) test and business centres, with extensive testing possibilities and an ecosystem of research, start-ups and corporations. Construction started at this decommissioned military airport in December 2017 to create a unique ecosystem, infrastructure and services to facilitate research, innovation and entrepreneurship in the aerospace and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) market. DronePort Incubator aspires to be the home for start-ups, organisations and research teams developing, producing or servicing the new drone economy, promoting cross-pollination between research and product development.

Other Belgian initiatives includeDrone Valley in the south of the country. One of its projects is the establishment of a UAS airworthiness test facility for drone safety, durability and cybersecurity. The centre aims to offer independent performance and safety benchmark testing for drones and drone-related products, supporting industries involved in the production and use of drones in Europe. Test results will be used to establish performance-based standards for unmanned systems operating in the European Airspace System. To offer this service, the centre will rely on the (re)use of tangible assets (satellite/broadcasting infrastructure and suitable airports with segregated airspace), specific skills and proven experience provided by third-party companies.

In Ostend, there’s a Belgian initiative called the H3-One Drone Port, currently in the planning stage, which aims to optimise drone operations and help boost all aspects of development of the new aviation market, revitalising the airport and surrounding area.

The Belgian start-up scene is also an important contributor to the development of the drone ecosystem. Omar Mohout of Sirris shared the following data in early 2018:

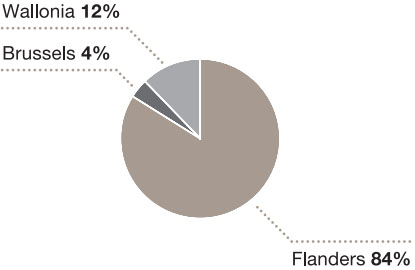

Belgium has an active drone start-up/ scale-up landscape, with 25 identified start-up and scale-up companies developing hardware and software in 2017. The geographic distribution is as follows:

After limited access to funding in previous years, a peak of 6.7 million euros was raised in 2016, of which Unifly secured the largest portion.

To assess the success of all these initiatives, possible metrics would be job creation and the broader positive knock-on effects for the economy as a whole.

Service providers

A growing number of service providers, predominantly start-ups to scale-ups, are active in Belgium. Increasingly, we see them developing specialised services, such as inspection of windmills and solar panels, mapping, photogrammetry, agriculture applications, etc. Our research found that many companies value these applications as ‘drones as a service’ and engage with service providers rather than developing the competences themselves.

Regulatory environment

Drone legislation and its incorporation into national law falls under the remit of the Federal Public Service (FPS) Mobility & Transport and the corresponding minister. In addition, once finalised, European Union (EU) legislation will be introduced in all Member States and will gradually replace national legislation.

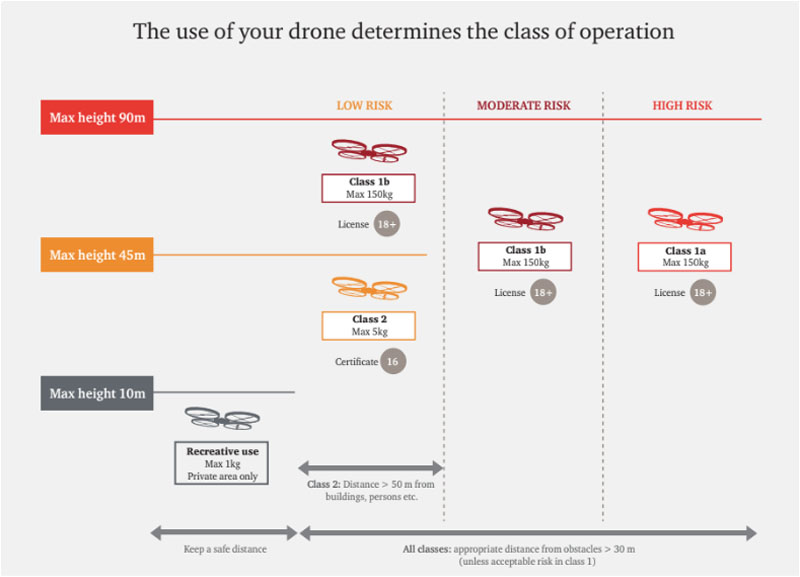

FPS Mobility & Transport, and specifically the BCAA, is the key regulator for safe drone flights in Belgium. Its main tasks are to authorise drone flights with respect to Belgian Drone Law, organise theoretical drone exams and issue pilot and drone licences. A dedicated drone cell10 has been put in place by FPS Mobility & Transport and Belgocontrol to help drone users by offering information on drone use as well as an interactive airspace map to both professional and recreational drone users in Belgium. In anticipation of upcoming European drone legislation, the contribution made by the Belgian legislator is highly valued. As Figure 6 illustrates, flexible and efficient regulations are proving to be a key contributor to the growth of the drone ecosystem.

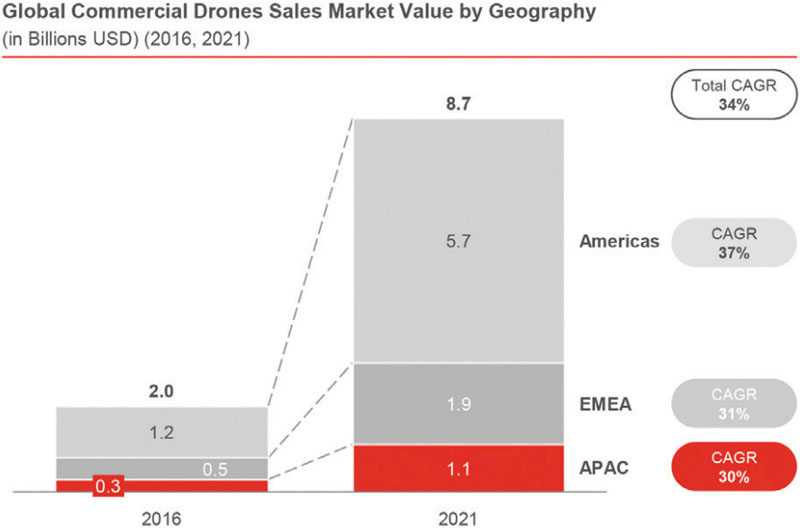

The strongest growth in drone-related business to date has been in the Americas, partly as a result of highly market-focused and flexible regulation.

Training and education

Safe drone flights require educated, certified pilots. The ecosystem also requires knowledgeable people in a wide variety of roles including maintenance, innovation and development of products and solutions.

There’s a growing selection of drone-specific training courses and research activities within the Belgian higher education system, in universities such as VIVES, KUL, UGent, UA, VUB, UCL, ULB and UNamur.

With nearly 500 certified drone pilots in Belgium and counting, both established schools like Noordzee Drones, BAFA, EspaceDrone, the Belgian Drone School and newcomers alike have their hands full. Some are beginning to specialise in specific use cases like agriculture and inspections, or in rapidly evolving domains like thermography and photogrammetry.

Applied research

Vlaamse Instelling voor Technologisch Onderzoek11 (VITO) has been at the forefront of drone experimentation for over 15 years. It built its own drone early on and is currently undertaking landmark initiatives while working with private companies, universities and international research and development (R&D) and innovation hub IMEC. VITO combines profound knowledge of drones with a multidisciplinary approach which often leads to unique solutions that would be infeasible with only a unilateral approach. Unifly, a spin-off of VITO, is proof of the value of – and need for – such organisations.

VITO is not alone in the Belgian landscape: a number of universities are active in drone innovation and applied research. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (KUL), for example, took the lead in Cargocopter, an innovative generic drone concept designed and 3D printed to suit challenging demands like package delivery. A payload of up to 5 kg, flight range of 60 km and speeds above 100 km/h are possible with this patented hybrid concept that combines wings with a multicopter, and makes a transition from hover to forward flight. This allows for fast and efficient flight like an airplane, while still being able to land and take off vertically with precision positioning within 50 cm. The need for interdisciplinary collaboration for innovations like Cargocopter is growing.

The evolution of these much needed initiatives can unfortunately be hampered by a fragmented approach and lack of sufficient long-term commitment and funding. Access to European projects however, in the context of Horizon 2020, is creating new opportunities.

Collaboration, networking and community building

Working together to find your way in a new and promising ecosystem is essential. Drone stakeholders need encouragement and support in their endeavours. Belgium, like other countries, has a number of initiatives to this end. Below are the main projects currently active (in alphabetical order).

Agoria

Since 2015, Agoria has been active in developing the drone economy in Belgium. Agoria connects and collaborates, stimulating innovation and fostering the development of value-driven industry applications. It lobbies for the positive application of the Belgian Drone legislation and actively supports the implementation of the new European legislation. Agoria has a seat on the Board of the Belgian Drone Association, BeUAS, and has recently been recognized by The Bureau for Standardisation (NBN) as a sector operator for ISO/TC20/SC16 “Unmanned aircraft systems”. It also sits on Imec.istart’s vertical “Aeronautics & Drones” Advisory Board. More info at www.agoria.be.

Belgian Unmanned Aircraft Systems Association (BeUAS)

BeUAS12, a non-profit organisation, was founded in 2012 and is the National Federation for Unmanned Aviation. It defends the interests of all Belgian public and private sector organisations, large and small, active in the development of the drone ecosystem. It contributes to the safe integration of drones in the air and is actively engaged with local, European and international stakeholders. For its 500+ members, it provides consulting, networking, lobbying and a cost-competitive insurance policy offering. Agoria and Vlaams netwerk van ondernemingen (VOKA) both have seats on the board of directors.

Drone Valley

Drone Valley13, a non-profit organisation embraced by Digital Wallonia, brings together all players in the drone value chain from requirements analysis to solutions. One of Drone Valley’s major initiatives is the development of a key enabler of the drone economy, namely UAS airworthiness test facilities for drone safety, durability and cybersecurity. The goal is to offer independent performance and safety benchmark testing for drones and drone-related products for industries involved in the production and use of drones in Europe.

EUKA

EUKA14 is the Flemish drone cluster that brings the drone industry and end users together to create a business platform through targeted partnerships with various federations, knowledge institutions and governments. In 2017, it was awarded an IBN project from the Flemish government. EUKA works according to the ‘triple helix’ model and aims to create a hotbed for innovative, drone-related ideas in Flanders. Through events, learning networks, seminars and creative sessions, EUKA facilitates the sharing of knowledge and experience necessary to provide the new drone economy with the opportunities it needs to grow.

Commercial applications

Agriculture

Precision agriculture – the aim of which is to optimise harvests – has already found its way into the Belgian market. Data plays an important part in precision agriculture; based on observation and measurement, a farmer decides when and how to treat each crop. Precision farming involves many techniques and tools, and drones could be one. However, drones have as yet failed to impress Belgian farmers for a number of reasons:

- Belgian legislation on drones limits possibilities. Drones aren’t allowed to transport things so can’t be used for watering or fertilising crops, only for monitoring and measuring

- Farmers are rather sceptical towards new technologies and tools, including drones. Currently, it’s mainly Belgium’s agricultural research institutions that are experimenting with drones to

see where they could add value and outperform other tools. Once there’s a proven ROI, farmers are likely to trust their advice and start implementing drones in their operations

The question remains as to whether farmers will invest in drones themselves or rely on third parties. Most farmers have small agricultural plots (< 50 ha) and are only interested in two to three flyovers a year15. The cost of a drone is too high for small farms so the market will be mostly for ‘drones as a service’.

Overall, PwC and Agoria estimate the current addressable market value of drone-powered solutions in the Agriculture industry to be 29 million euros.

Faster detection of diseases

Agricultural diseases, such as fire blight in apples and pears, can have devastating and costly consequences. If not detected early, the bacteria can destroy a whole orchard. Drones are seeing significant usage in the detection of such diseases. Equipped with a hyperspectral camera, drones could detect fire blight before it’s visible to the human eye. Fast reaction is key to allow the farmer to control the disease and limit damage. Pilot research projects have already been conducted in Belgium, and agricultural research institutions are looking to refine results and optimise drone use

for this application. The potential benefits for the farmer are substantial. Connected to an alert system, a drone could save a farmer significant time by autonomously detecting diseases.

More efficient scarecrow

Other than fruit diseases, aggressive birds, such as crows, are also a real pain to farmers, destroying and eating crops, and impacting harvests. Drones could be used as scarecrows, flying above orchards and fields. For maximum impact, an autonomous drone that can detect the birds’ presence could be launched when the birds are already on site. If the drone only appears at fixed times, birds are smart enough to adapt their schedule to avoid it. This is a relatively easy application that could be commercialised very soon, if legislation would allow.

More precise monitoring of cultivation

There are a lot of processes involved in crop lifecycles and there’s room for drones in each, from soil analysis and seed planting to choosing the right moment for harvesting16. Most Belgian pilot drone projects have focused on monitoring cultivation. Data captured is used to compare crop varieties, detect correlation trends and optimise the fertilisation process. Drone technology offers qualitative crop data. Farmers used to take a sample of each garden plot. With a drone, one image is sufficient to monitor crop health and progress, offering efficiency gains and allowing the farmer to focus on other activities.

More precise harvest estimation

In cultivation, the farmer must know flowering intensity, as the number of flowers determines the expected yield. The thickness of the fruits is also important to give an idea of the quality of the harvest. Based on this data, the farmer can decide how many fruit pickers to hire and how many fridges to book. Harvest estimation is currently a manual endeavour and is not just time consuming, but expensive, subjective and inaccurate. Drones could automate this process by using high-resolution sensors or smart cameras that count the number of fruit and measure the thickness of each, thereby estimating the harvest. Projects are ongoing to improve accuracy in this application.

Harvest optimisation in the future

If the legislation would allow the transportation of products, drones could replace the current method of fertilising plants. Today, irrigation solutions take up room, leave spray traces and damage the soil, and crops near the spray traces tend to be of lower quality than others. Drones, which don’t damage the soil or leave spray traces, could result in up to 10 percent more space for crops and more consistent quality, allowing farmers to yield significant increased sales.

Agriculture is becoming a highly data- driven industry and it’s expected that a Big Data platform will be developed via which data can be shared amongst farmers. Data captured by drones could definitely provide input.

Proefcentrum Fruitteelt inspires the industry by experimenting with drones

Proefcentrum Fruitteelt (pcfruit), a research institution within the Belgian agriculture industry, is working with universities, other research institutions and the industry to conduct research projects on several topics, one of which is drones. Among other topics, they’re investigating the value drones could add to farmers in any of the applications mentioned above. Once they’re convinced that value can be added, they’ll advise farmers on how to use drones for that application.

Given farmers’ scepticism, it’s important that such institutions take up the role of trusted advisor and help guide farmers towards innovation that works, thereby fostering the use of new and emerging technologies within the sector.

“As Agriculture is an industry that’s becoming highly data-driven, drones will be an important additional tool to increase the efficiency of data gathering.”

– Michael De Roover, Partner, PwC Belgium

Energy & Utilities

One of the Belgian industries most enthusiastic about using drones is the Energy and Utilities (E&U) sector. And it should be: drones offer a lot of potential, supporting various business operations ranging from creating 3D models to conducting inspections. Various (pilot) projects have proven the added value of drones in terms of safety, cost efficiency and quality. The industry is avidly experimenting with drones, discovering new applications and exploring how to use them to their full potential. We estimate the addressable market value of drones within the E&U industry to be 23.3 million euros, and that’s just the beginning.

More accurate 3D models via photogrammetry

Thanks to 3D modeling, reconstructions and visualisations can be made of assets. 3D models are created via photogrammetry, defined as “the gathering of measurements in the physical world by way of computer analysis of photographs”17. In other words, photogrammetry lies at the intersection of geometry and photography. Drones are used in this process to capture pictures of assets

and installations. A wind turbine engineer, for example, can build such a model to visualise the construction of a particular windmill. The pictures would then be processed by software, which transforms them into a 3D point cloud and then into a solid 3D model. These models can be used, among other things, to perform virtual visits of the assets or to better prepare for maintenance visits. Data is captured faster and assets modelled more accurately, improving the efficiency of the workforce.

Increasing safety during inspections

Maintenance is a major aspect of the E&U sector. All utility lines and masts, wind turbines, solar panels, etc. must be inspected on a regular basis to avoid disruptions. Most of these inspections are performed at height, either by patrols of maintenance staff climbing masts or via helicopters. Although efforts are made to ensure safety while executing these activities, a risk of falling and other dangers persist. By shooting photos and videos of the installations, drones mitigate these risks. Inspections are also greatly facilitated with drones: they’re faster and allow a more complete,

comprehensive and accurate view of the installation. Footage of the assets can be analysed in detail, on the spot or afterwards, which isn’t possible with human inspections. Drone inspections also minimise downtime. Human inspection may require an installation to be turned off, which causes inconvenience. Drones allow inspections without downtime. These advantages have a major impact on overall maintenance costs, leading Belgian companies to embrace drones in their inspection processes. Many are experimenting with drones for the inspection of utility masts, windmills, solar panels, etc., while some are going one step further by implementing drones in their day-to-day operations. Due to legal restrictions (e.g. not flying beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS)) and limited battery life, drones are used more for inspection of static assets rather than of long linear assets, such as electricity grids or pipelines. Today, the latter is done by helicopters or by travelling field teams. If the regulations changed, it would only be a matter of time before drones could inspect the entire Belgian utility network.

Elia was granted an exception in March 2018 to conduct what turned out to be a successful long-distance demo flight to inspect its high-voltage grid using a fixed-wing drone. The goal was to prove that a long-distance (BVLOS) flight can be conducted safely, in the hope that the legislation will be adapted and long-distance flights will be made possible. If that were the case, Elia would integrate drones in its day-to-day operations, enabling visual checks and damage assessment in the event of power outages.

In addition to having a camera for taking pictures and videos, drones can also be equipped with a sensor to detect gas leaks or a thermal imaging camera to check faulty solar panels. Drones could also be used to make long-distance light detection and ranging (LIDAR) scans to create 3D models of a utility network.

As well as increasing efficiency and safety, drones also make it possible to analyse the situation in real time as the results are shown on screen while the drone is flying. Take incident response, for instance: when an incident occurs, e.g. a tree falls on a utility line, the current procedure is to send a field crew to the scene to decide what’s required to resolve the situation. In future, drones could be sent out for an initial assessment of the damage to determine the equipment and crews to be dispatched. With the appropriate legislation and technology, maintenance inspections and diagnostics could be performed by automated drones with advanced AI software to perform analytics and support maintenance processes, such as diagnostics in inspections. The drones could be supervised from a control centre and used for continuous 24/7 monitoring, resulting in a very accurate overview of the status of the utility network, and allowing for rapid response in case of irregularities. These applications are just the beginning: the industry is confident the future will reveal many more.

ENGIE Fabricom innovates its operations: using drones to install high-voltage lines and clean insulators on high-voltage cables

For over 70 years, ENGIE Fabricom has been the benchmark for the design, installation and maintenance of multi-technical facilities and services. Harnessing extensive knowledge of infrastructure, buildings, industry, distribution networks and energy, ENGIE Fabricom delivers total solutions tailored to the needs of businesses and local authorities. The company takes a customer-oriented approach and seeks out new, innovative solutions to meet customers’ specific needs.

For its distribution activities, specifically those related to high-voltage pylons, ENGIE Fabricom started testing drones in specific pilot projects in recent years. In 2016, for example, the company tested the use of drones in the installation of a high-voltage line for Elia as part of the Stevin project in Eeklo – a first for Belgium and a success for the teams involved. Belgium has stringent legislation on drones, so the government granted special permission for this test case installation. Using drones offers significant benefits: they’re less risky, faster and less expensive than a helicopter.

A test programme is also underway using drones to clean insulators on high- voltage cables, a task currently performed by maintenance personnel who have to climb to the top of pylons to complete the task. Together with the ENGIE Group Research & Development team, the solution is currently being optimised. The use of drones has the potential to greatly increase efficiency.

The drone’s eye view in E&U

Koen Hens, Partner, Energy & Utilities Leader, PwC Belgium

Drones are poised to revolutionise the E&U sector in Belgium. In a country with relatively high labour costs, drone technology can reduce expenditures while improving safety and efficiency. Koen Hens, Partner and and Energy & Utilities Leader at PwC Belgium, explains: “The E&U sector in Belgium – and worldwide – is under unprecedented pressure to move toward a less carbon-intensive economy while lowering energy prices. As industry players struggle to maintain profitability despite these challenges, the stage is set for the implementation of drones to not only protect people, but also operating margins.”

The potential of drones to streamline processes in the field is significant. They can live-stream video and capture high-resolution and thermal images of a facility, including hard-to-access areas that would otherwise be monitored by costly planes or helicopters. Drones can perform power plant inspections and maintenance tasks that are difficult or even dangerous for humans, without the need to cut off the power supply while doing so. These advantages are crucial in the face of tightening government regulations and financial incentives for companies that hit – or miss – reliability targets. Site monitoring by drones is quicker, safer and significantly cheaper. Belgian energy companies are already pioneering the use of drones for tasks such as inspections of high-voltage grids, thermal power plants and solar farms – setting an example that competitors are likely to follow soon.

“As industry players struggle to maintain profitability, the stage is set for the implementation of drones to not only protect people, but also operating margins.”

– Koen Hens, Partner, Energy & Utilities Leader, PwC Belgium

Entertainment & Media

The Entertainment & Media (E&M) sector in Belgium has experienced strong growth thanks in part to digital technologies like social media, mobile apps and drones. Drones offer creative new angles in audiovisual production and can have wide application in the advertising industry. PwC and Agoria estimate the current addressable market value of drone-powered solutions in the E&M sector to be 45.7 million euros.

Cost-effective aerial photography and videography

The most common use of drones in the E&M industry is aerial photography and filming. Drones offer new storytelling formats by enabling dramatically different angles, like shooting video over water or while flying through trees. They’re used in television, advertising, live sports, news reports and more. Drone use by corporations is also on the increase, for producing corporate video footage and photography for marketing purposes.

Using drones offers numerous advantages over traditional methods of capturing aerial imagery, usually by attaching cameras to cranes or helicopters. One is ease of use: drones require minimal setup and only one person at the controls, while operating a crane requires significant setup and at least four people. A helicopter can’t get too close to the subject due to its size and the large amount of noise and wind it creates – much more than a drone. Another advantage of drones is their flexibility in changing angles, a technique frequently used in videography, which takes a great deal more effort to do with a crane. Finally, their relatively low cost compared to cranes and helicopters tips the scales in favour of drones for shooting aerial photography or videography.

Creative ways for brands to connect with customers

Drones are playing an increasingly important role in the advertising industry as they provide new and creative opportunities to capture the attention of brand audiences. One of the techniques, called ‘airvertising’ or aerial advertising, is to attach banners with promotional messages to a drone and fly it at events or even in the streets – more dynamic and eye catching than a static poster. In addition to banners, Belgian advertising agencies are also offering drones carrying LED screens. Trendy brands are now using drones at events for people to take aerial selfies.

New entertainment activities

Drones have potential in the entertainment industry as well beyond merely relaying images at sporting events, for instance. The rise of drones is spurring new entertainment activities like drone racing, in which pilots race drones against each other. Drone racing in the United States is experiencing tremendous growth and is surpassing audience ratings for Formula 1 auto races19. In Belgium, drone racing is still very much in its infancy, although races have been held in Tour & Taxis in Brussels and in decommissioned factories in Liège. The industry expects that it’s only a matter of time before the trend takes off more widely here too.

Another new form of drone entertainment is drone light shows that feature a fleet of drones flying in formation, each carrying a LED screen that together create a larger image. The 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang were opened and closed with a drone light show – the opening ceremony saw a record-setting 1,218 drones in synchronised flight20. In Belgium, several requests for drone light shows have been initiated, largely by cities and municipalities wishing to showcase their commitment to innovation. The industry expects an increase in demand and that drone light shows will equal and perhaps exceed the popularity of fireworks displays.

More effective marketing campaigns

Drones offer a wide range of possibilities for innovative marketing initiatives, which will broaden once they’re allowed to carry objects. For example, drones could be used to distribute samples – imagine sun cream samples being distributed on the beach. Drone technology combined with face-recognition technology for targeting specific audiences like children, the elderly or people with specific skin conditions would significantly increase the value proposal: creative branding combined with more effective targeting.

“Drones provide the medium to tell a story from a fresh, new angle, both literally and figuratively.”

– Lieven Adams, Managing Partner Advisory, PwC Belgium

Spicymotion spices up live events with tethered drones

Spicymotion is a marketing and communications agency known for its innovative advertising solutions and media experiences. It’s also one of the first companies in Belgium to offer tethered drone services, a marketing tool with a wide range of possibilities for all kinds of organisations. At large gatherings like festivals, Spicymotion films happenings with a drone tethered to a fibreglass power cable. This addresses safety concerns by ensuring the drone can’t fly away, and maintains a safety perimeter of eight metres at all times while never flying above visitors, mitigating the risk of injury to the audience. Since the cable restricts the movement of the drone and limits piloting errors, there’s also no need for a trained pilot – a big advantage for Spicymotion, as anyone can manage the drone. And, tethered drones can remain in the air continuously as power is transmitted via the fibreglass cable, eliminating the need to land every 15 minutes to change the battery.

Infrastructure

Using drones to help manage infrastructure makes real sense. The construction industry – for construction sites, roads and railways – has already discovered the many ways in which drones can add value and is already reaping the rewards. Not only can drones perform hazardous work, but they also collect data accurately and in a cost-efficient way.

PwC and Agoria estimate the addressable market value of drones in the Belgian Infrastructure industry to be 176.3 million euros.

Fast and accurate inventory management

Players in the infrastructure sector need vast amounts of assets delivered and store them on their premises, some of which cannot be measured by the human eye (e.g. piles of sand). The volume of such assets can easily be gauged using drones, making inventory assessments faster and more cost-efficient, and much more accurate.

Cheaper maintenance inspections

Maintenance is an inherent part of infrastructure management. Today, much of this work is carried out manually via in-person inspections, a slow and costly process that yields incomplete and poor-quality results21. Drones can be used to take pictures of infrastructure so that its condition can be analysed. Delivering a close-up view of damage means an owner can more easily determine which maintenance technique to use and likely costs. Not only do drones cut inspection costs significantly, but they also enable inspection in places that humans would find difficult to reach.

Transparent investment monitoring

Investment monitoring is a complex process consisting of several stages, drones could be used to automate part of the work:

- Before construction starts on a mobility solution, for example, a drone could carry out research by mapping traffic flows to determine where bottlenecks are. This would support a decision as to whether or not a big construction project should be approved.

- During the pre-construction phase, drones can be used to take pictures and record the ‘as-is’ state. Measurements can be processed and used to create a 3D model, delivering an accurate overview of the whole area. Such a model makes it easier and more straightforward to explain to stakeholders what work needs to be undertaken (e.g. damage to be repaired). It also offers those carrying out the repairs a clear visualisation of what needs to be done. With every stakeholder using the same information, transparency and consistency in communication is improved.

- During the construction phase, drones can measure progress or change by comparing current state to a baseline measurement already taken. Drones facilitate quick and accurate checks as input for progress reports. Discrepancies between the current state and initial plans can be seen in detail, enabling construction works to be followed up and documented in a very transparent way. Drones can provide trustworthy documentation in case of disputes.

- Pictures taken by a drone, especially from above, of progress and the final state can be used for marketing and communication purposes, costing much less than if a helicopter had been required.

Simulations and intelligent analysis in the future

A new application that’ll most likely find its way into the infrastructure industry is simulation via drone footage. Using 3D simulations can help prepare people for certain missions, avoiding the need to go on location numerous times. 3D models also form the basis for virtual and augmented reality (AR). Via virtual reality (VR) glasses, spaces can be discovered virtually, delivering huge benefits in terms of cost and safety.

VR and AR aren’t the only emerging technologies that could be combined with drone technology. Using AI, a computer could analyse drone images and report which images show damage.

Hoogmartens wants to take its operations to the next level

Hoogmartens is a construction company focused on exterior infrastructure (e.g. roads) that’s constantly striving for greater innovation. It’s one of the first companies in Belgium to use drones in its day-to-day operations. Its geometricians use drones to increase efficiency in a number of ways; they use drones to measure inventory and on-site progress, and to map roads and assess the condition of infrastructure (where and what damage?). Using measuring points, drone software can also calculate the amount of asphalt, for example, that’ll be needed to repair the damage. This in turn makes the proposal process much easier and more efficient as the accurate data reported by the drone can be used as input without experts having to leave their desks.

Hoogmartens is already convinced of the advantages drones can bring to optimising its business processes and help the firm move forward in terms of communication speed, safety and transparency. However, there are two barriers preventing Hoogmartens using drones more than it does already; legislation and data analysis capabilities. Hoogmartens undertakes a lot of work for the government and carries out a lot of renovations of public roads. As drones aren’t currently allowed to fly over public domains, it can’t use drones for these projects.

Hoogmartens also feels that data analysis software is lagging behind. Data collection (point clouds) is not an issue, but intelligent assessment software is lacking. Today, Hoogmartens exports created point clouds to AutoCAD, for example, to undertake the next steps. To get around this, Hoogmartens is developing its own software to indicate where the damage is and analyse and interpret the situation. This will be a big step forward in fostering the abilities of drones and enabling the company to use drones more extensively in the future.

Infrabel won a prize for using new technologies to maintain its railway infrastructure

Matthias Reyntjens, Partner, PwC Belgium

According to PwC’s global report ‘Clarity from above’, the average construction site monitored by drones has decreased its life-threatening accidents by up to 91%. PwC and Mainnovation has awarded Infrabel, the Belgian rail infrastructure management company, a prize for its use of new technologies for the proactive maintenance of its railway infrastructure.

Pressure to improve the safety and reliability of rail infrastructure has increased for a number of reasons:

- Safety is paramount. To improve employee safety, for example, Infrabel is looking to reduce the number of visual inspections undertaken by maintenance crews walking along the tracks.

- The railway network is becoming increasingly strained. Not only due to an increase in passengers and freight trains, but also because new high-performance trains exert greater stress on the tracks. A busier schedule also means a smaller window of opportunity for maintenance. Planned downtime must be communicated to railway operators a couple of years in advance.

- The general public and governments demand greater safety and accuracy. Every incident generates negative publicity for Infrabel and further increases pressure to prevent future incidents.

In response to these challenges, Infrabel has invested heavily in automating a number of maintenance processes. It’s become exceptionally strong in developing innovative condition monitoring tools and it’s recently been experimenting with drones to inspect the rail infrastructure. Drones are currently used mainly to control GSM-R masts.

The areas in investment monitoring of large constructions in which drones could add value are clear and plentiful, including maintenance inspections, asset inventory registration and the execution of specific hazardous and dangerous maintenance or repair tasks.

Infrabel is also considering automatic verification of the heating of a switch heating system using thermal cameras or equipping a drone with a 40-million-pixel camera that could assess the condition of nuts and bolts, whether they’re well fixed, if there’s corrosion, etc. This would limit train service disruption and with antennas left in operation would also improve security, alongside quality and punctuality. Drones can carry out inspections and surveys more quickly, more cheaply and more safely than people or helicopters, reducing overall insurance costs. And they perform tasks more thoroughly. Drones will be a vital technology in the infrastructure sector over the years to come.

“Thanks to their cost and safety gains, and the numerous applications in which they can play a role, drones will be a vital technology in the Infrastructure sector over the years to come.”

– Matthias Reyntjens, Partner, PwC Belgium

Insurance

Insurance is, at its core, a business of assessing, preventing and mitigating risk, and insurers are constantly looking for better information about the assets they insure. For a building, for example, that can be when assessing how much it should cost to issue an insurance policy (underwriting), what damage occurred (claims) or, in the best-case scenario, preventing claims before they happen

(risk mitigation). Using drones to gather photos, video and data about a property is a big leap in the technology behind this process.

Early adopter cases include usage by two American insurance companies – Erie Insurance and Allstate. In 2015, Erie Insurance received the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) nod to deploy drones to automate and accelerate underwriting and claims processes. A year later, Allstate, in a pilot conducted in Texas, US, deployed Quadcopters to assess home damage in hailstorm-affected areas.

Although most insurers are convinced of the benefits drones can bring to their field operations, the following challenges are keeping them from moving from the experimental phase to full operational deployment:

- Regulatory compliance

- Management of a drone fleet or contracting/managing outsourced drone services

- Making drones just another tool in an adjuster’s tool belt so that they’re easy to deploy in the field.

Drones offer insurers a growing number of potential benefits, such as helping reduce injuries and the cost of workers’ compensation claims. By putting drones, rather than people, in hazardous situations, insurers can prevent some on-the-job injuries. Drones can also help reduce costs. Roofs can be costly to inspect, especially when harnesses and other safety equipment are required for adjusters to carry out a safe inspection. Using a drone would be more cost- effective. Drones can also help insurers save money following a disaster. Using a drone to capture images means fewer adjusters are needed to inspect damage at the disaster site. The insurer may reap substantial savings as adjusters can remain in the office to review the data (a far greater set then before) and process claims faster.

Drones can also help prevent risks. With their 24/7 surveillance ability, drones can quickly identify threats from natural disasters, such as volcanic eruptions, floods and hurricanes. This real-time surveillance data can be used to rapidly send disaster advisories and alerts to affected areas.

Drones will also benefit customers. As drones can confirm the existence of features that make properties more (or less) risky to insure, personalised premium amounts can be quickly calculated based on far more precise inputs into pre-defined pricing algorithms. And the use of drones can lead to greater customer satisfaction. Able to take more photos in less time than a human, by using drones to capture loss data, insurers can process claims more quickly. Policyholders express more satisfaction with their insurers when claims are paid promptly.

In the near future, drones, with their ability to quickly gather large volume data across terrains, will be able to reduce fraudulent claims.

Overall, the real benefit of drones for insurance companies comes from the potential gains in safety and efficiency. Companies can move from dangerous, hands-on, time-intensive jobs, like

property inspections, to a quick, safe and much faster process that allows their workforce to keep both feet firmly planted on the ground.

Recognising the game changer potential of drones and a revised drone-friendly regulation, combined with the success of early adopter pilots, should drive drone usage across the insurance value chain. The outcome will be streamlined and optimised property and casualty insurance processes, delivering a game-changing customer experience and a far greater competitive landscape.

PwC and Agoria estimate the current addressable market value of drone-powered solutions in the Belgian insurance industry to be 40.6 million euros.

“Drones enable insurance companies to assess risks better and faster than ever before, resulting in more accurate premiums and happier customers.”

– Dirk Vangeneugden, Partner, PwC Belgium

“We’re seeing insurance companies around the world incorporate drones into the claims process with success. The results are too positive for companies to ignore.”

– Mike Winn, DroneDeploy CEO, during a recent interview with Insurance Tech Insider

Safer roofing and damage inspections

One of the most common uses for drones by insurers is conducting rooftop inspections. Roofs are notoriously difficult and hazardous to inspect. An inspection is particularly dangerous if a roof is steep or has suffered fire damage. An adjuster can avoid climbing onto a roof by using a drone equipped with a camera to provide detailed images. A drone can also photograph the entire roof, including parts of the structure that aren’t accessible to humans.

Faster post-disaster claims inspections

Drones can inspect areas affected by major disasters, such as floods and earthquakes. Access to disaster areas may be restricted by civil authorities for several days or may simply be too dangerous for adjusters to enter. Adjusters can use camera-equipped drones to capture still photos or videos of damaged property which can then be used to process claims.

Easier insurance inspections of properties that are extensive or difficult to reach

One possible use for drones is to conduct property insurance inspections. Drones could be particularly useful if the insured property is extensive or difficult to reach. For example, a crop insurer might use a drone to inspect a farmer’s crops. Certain issues may be easier to spot from the air than from the ground. A drone’s camera can be equipped with special lenses to detect problems that aren’t visible to the human eye.

Effective fraud monitoring

Drones could also be used to deter insurance fraud. For instance, an insurer could send a drone to take photos of an accident scene. It could then use the data collected to verify details submitted by the insured in a claim.

Drones in service @ KBC Insurance

Kim Moors, Product Manager & Lawyer

KBC Insurance, part of KBC Group NV, is a frontrunner in the use of drones. In 2017, it started using drones in Belgium for claim management purposes in property, for example after a big storm. Multiple large buildings and factories can suffer damage in a storm and it’s almost impossible for an expert to inspect every building, especially those with large roofs, pointed church towers and other complicated buildings. A drone can inspect these kinds of properties in a few hours, with no need for aerial work platforms, climbing cables and other materials, significantly reducing safety issues.

Drones provide KBC Insurance with highly-detailed and accurate data, which affords it a good view of the claim and allows it to assess damage quickly, precisely and in a safe and cost-effective way. As drones aren’t used that frequently and the expected evolution of the technology is rather fast, KBC Insurance works with external Belgian drone services partner Argus Vision. The partner delivers a 3D model and individual detailed pictures which KBC experts inspect to assess the claim. There’s very little room for error. The pictures can also be sent to customers as proof.

What’s next?

KBC Group is currently setting up an experiment in risk assessment using drones. The intent is to inspect large property risks (before it agrees to insure them), validate if the property’s overall state meets its standards and provide future customers with valuable information about the property in the form of 3D models, individual pictures and an inspection report.

This gives KBC the opportunity to set better premiums for customers. Today, its risk engineers are unable to inspect the outside of large buildings and offer detailed pictures in just a few hours. This is where drones come in. The risk engineers simply have to take the results and process them, at no risk to themselves.

But drones can’t do it all. To date, drones have been unable to detect asbestos spread in the case of fire or get a clear view of damage in the contaminated area, for example. But KBC Insurance is convinced that drones can provide better (at least more) information. While the drone is important, KBC Insurance considers the quality of the data-capturing tools (sensors) and linked software for analysis as key differentiators. KBC Insurance is convinced that drones can help it improve customer satisfaction.

Security

Threats and thefts are becoming increasingly complex, requiring more advanced security solutions. Drones have a real role to play here, alongside better cameras and new technologies such as facial recognition.

Drones could be used for various security applications, ranging from supporting guards, policemen and firefighters during interventions, to monitoring goods and sites, preferably autonomously. Because human involvement will always be required, drones won’t be a disrupter. Instead, they’re more likely to be an additional support tool.

The industry is looking to regulators for a framework that fits its desire to use drones in day-to-day operations. Already, key industry players are setting up drone pilot projects to make sure they’re ready to meet client requests as soon as they legally can.

Not only does the Security industry have to come up with proactive applications for its sector, but must also provide an answer to drones being used with bad intentions. Safety is crucial in the security sector and players are developing countermeasures for when drones are seen as a threat.

Overall, PwC and Agoria estimate the total addressable Belgian market value of drone-powered solutions within the Security industry to be 30.9 million euros.

Effective surveillance support

Theft of valuable goods is a serious problem. Many companies employ guards to monitor sites and use static cameras. Unfortunately, this too often results in unsurveilled blind spots. Although static cameras will remain important, drones could provide additional security by offering a dynamic view of the entire site. This would be especially useful at large sites. If drones could be preprogrammed to fly autonomously and at night, they could survey the site while a guard keeps an eye on screens in a control room.

And, if drones were equipped with not only a camera, but also a sniffer to detect gas or other toxic substances, for example, or a radio-frequency identification (RFID) scanner to manage inventory, they could combine multiple applications and further enhance their added value in a very cost-efficient way.

Drones could also be used for crowd or traffic control at public spaces or events (e.g. festivals). By monitoring flows, they could provide real-time data for security teams about congestion and disturbances. Able to identify risks and problems before they escalate, security teams would be able to react faster. Currently, for safety reasons, police and security companies avoid flying drones above crowds and stick within dedicated drone areas. In some cases, tethered drones are used.

When drones have the capability to recognise faces, their value at events could increase further as they could help identify wrongdoers.

Increased efficiency during interventions

Interventions are often dangerous as guards, police officers and firemen don’t fully know what to expect before they go in. Drones could play a major role by undertaking a first check of the situation and preparing those going in for what they can expect, having a potential lifesaving impact.

If legislation would allow drones to fly autonomously and beyond line of sight, a drone could fly to the scene when an alarm goes off to verify the situation and check whether it’s a false alarm or

not. If not, the police could be called immediately. The use of a drone would significantly improve response time, having a positive impact on the chances of catching the burglar red-handed. Drones could also help if an offender were able to flee the scene, helping identify where they’re hiding or which way they’re running.

In the case of a fire, a drone equipped with a thermographic camera could go in ahead of the firefighters to provide an overview of the situation and locate people who need rescuing, helping increase the efficiency of the operation and mitigate risks.

Countermeasures for drones used with bad intentions

The more drones are accepted in society, the higher the risk drones will be used with bad intentions. This could be as simple as a drone entering an area it’s not supposed to, or the use of a drone to deliver drugs, mobile phones or even guns to people in prison, and even the use of drones for terrorism.

The Security industry is working hard to develop a strategy to tackle such threats. Security companies can already detect drones that cross perimeters they’re not supposed to using devices that detect radio and wifi signals in a 360° radius, and within a distance of up to three kilometres.

Drone identification is also possible today, including the type of the drone and its mac address (the drone’s unique identifier). Once identified, it’s important to evaluate whether the drone is flying legally or not. For that, there needs to be a database of licensed pilots and flight permits.

The Security industry, together with clients, is also developing a 3D security strategy and underlying processes to be able to react faster when drones are a threat. The current struggle focuses on how to take control of the drone and get it out of the airspace safely.

A number of techniques have evolved, such as jamming, which is when a signal is sent out to disturb all wifi and radio communication within a certain perimeter. The drone then falls down. This can only legally be done by the police authorities. This technique clearly can’t be applied in no-fly zones at festivals or other locations where there are a lot of people as jammers can’t control where the drone will crash, implying a huge safety risk. Jamming is possible in remote locations, such as at sea.

Limburg police using drones to detect marijuana and provide support for traffic accidents

Limburg Province police department is already actively using drones in its operations, such as for the detection of marijuana. By attaching a thermographic camera to a drone, buildings with a higher-than-normal temperature can be identified. The accuracy of the thermographic imagery is 80%. Already a number of pot farms have been discovered. The aerial footage can also be used in court.

The Limburg police is also using drones to gain an overview of the situation and take measuring points when there’s been a large vehicle accident, aiding analysis and reconstruction of the event. Drones offer a faster and cheaper approach than helicopters, and can be employed more quickly. They also provide a more accurate assessment than humans.

The police department believes that the number of applications for drone usage will only increase in the future. It envisages the possibility of a static camera for facial recognition being set up at the border of the province to recognise criminals as they drive into the province. An autonomous drone could then be sent out to follow the car until the police gets to it.

Although drones have an important role to play in police operations and that’ll increase, they won’t eliminate other resources. The advantages they can offer mean that the tasks carried out by police officers will evolve.

The decision about which tool to use when will depend on the goal, and they’ll likely be used in tandem. For example, if someone is lost in a forest, a helicopter could be employed to provide a global overview. Once an area for a more detailed search has been identified, a drone could be brought in to provide more detailed footage.

“Drones won’t replace human guards, but can serve as an additional tool to make interventions more efficient.”

– Marc Daelman, Partner, PwC Belgium

Telecom

Telecom operators are uniquely positioned to become pivotal players in the rapidly developing commercial unmanned aerial vehicles (drone) market. Drones represent a unique opportunity to diversify their revenue sources and spur new growth. By means of a tailored strategy and implementation road map for commercial drone applications, drone solutions could become a key revenue source.

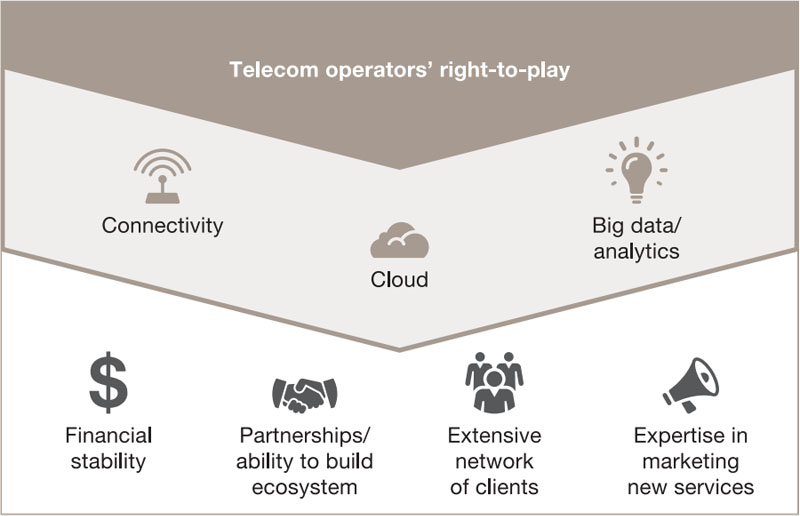

Reinventing themselves as digitisation players, Telecom operators have developed solid capabilities in Big Data and analytics, as well as in the IoT space, putting them in an ideal position to offer drone-powered solutions. They also have numerous other capabilities, such as financial stability, the capacity to invest, the ability to build partnerships and facilitate the drone ecosystem and undertake extensive market reach through their network of clients, as well as expertise in marketing and selling new products (see Figure 7).

Substantial expenditure in the telecom network and infrastructure will be necessary to support IoT connectivity, including the installation of reception devices on telecom towers using patented wireless data communication technology LoRa and the upgrade of the network’s software releases for long-term evolution (LTE) technology.

LTE and LoRa technologies enable tracking of registered drones via the attached dongle or chip. Drones that don’t use a dongle or chip could threaten the airspace because they’re not visible in the system. Their technical know-how and infrastructure enable Telecom operators to devise solutions that mitigate this risk, such as sensors (acoustic, optical and wifi), radio frequency detectors and radars to detect unregistered drones. These solutions would be complementary to (LTE and LoRa) network-based tracking.